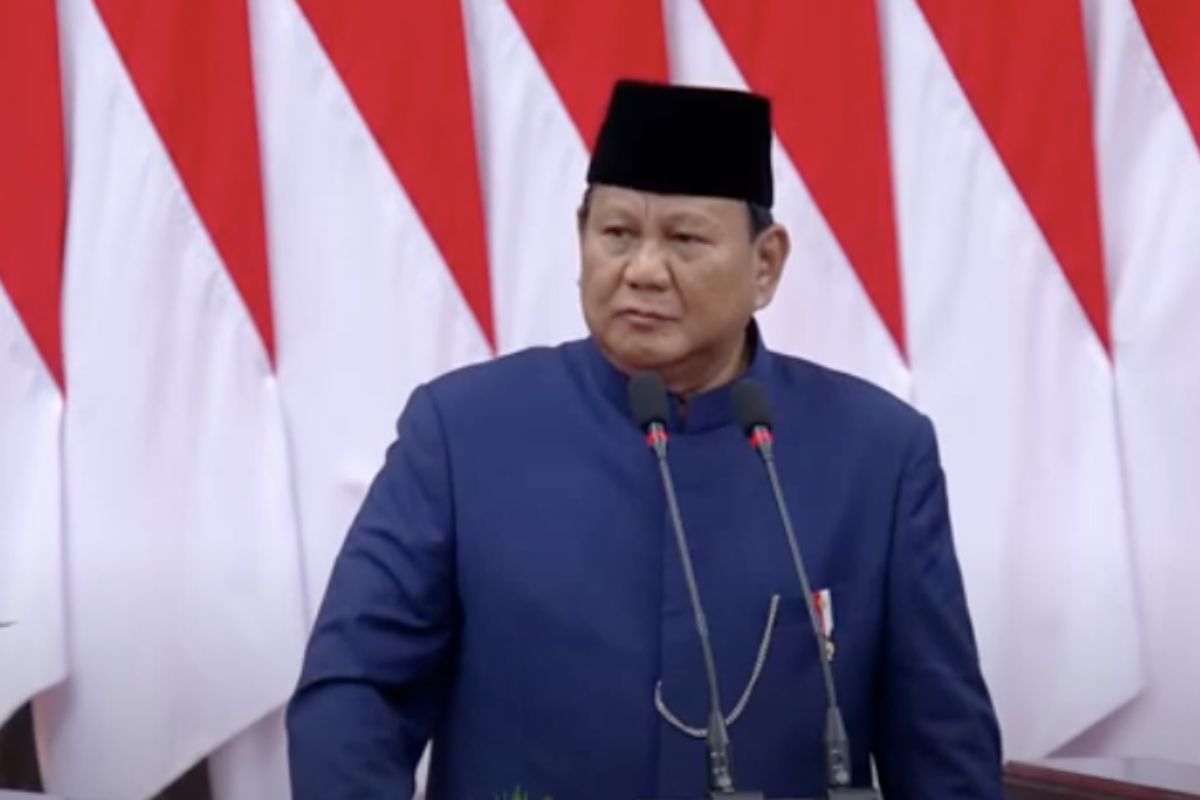

Indonesia’s new President Prabowo transformed by social media

Prabowo Subianto, sworn in as the eighth Indonesian President at the age of 73 , is proof that the old can connect with the young. The young supported him more than the old. The young on social media, that is. Especially TikTok.

Sworn in as president with the largest Cabinet in decades – a Cabinet of 48 ministries with 109 members — he has come to power with the help of social media and the support of his popular predecessor.

With clever use of social media, he has achieved what he couldn’t in his two earlier bids to be president – in 2014 and 2019. Leading his Gerindra party, backed by hardline Islamists, he lost both times to the outgoing president Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi.

Widodo, however, appointed him defence minister in 2019 and now he has been elected president with Widodo’s son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka , as his running mate.

So, it’s a vote for continuity.

Term-limited, after two terms as president, Widodo couldn’t stand for re-election and was succeeded by the man he supported, who teamed up with his son.

However, that interpretation doesn’t explain the magnitude of Prabowo’s victory.

He won by an even bigger margin than Widodo.

Prabowo won 59 per cent or more than 96 million votes in a three-way race — more than Widodo won in the 2014 or the 2019 election.

Amazing makeover

Behind Prabowo’s landslide victory is his amazing makeover on social media.

The former military commander who faced allegations of human rights abuses acquired the image of a fun-loving grandfather.

His brown and white stray cat, Bobby, became part of his sunny social media campaign which included even an Instagram account for the puss.

TikTok videos showed Prabowo doing his signature move – an awkward shuffle across the stage – or shooting hearts at the audience. Fans dubbed him “gemoy”, meaning “cute”, and called themselves the “gemoy squad”.

Social media endeared him to the young, a large constituency. Millennials and Gen Z make up more than half of Indonesia’s 205 million eligible voters – they also account for many of the 167 million Indonesians who use social media.

To reach the young, Prabowo’s official Facebook and affiliated accounts spent $144,000 in advertising over the three months up to the February presidential elections, the BBC reported, far more than his opponents.

The internet was filled with posters of Prabowo as a chubby cartoon character.

A spokesperson for his campaign said they were just trying to attract young people through a “fun” campaign.

“The logic is that Prabowo’s (earlier) losses were, at least in part, because his strongman image and firebrand style alienated parts of the electorate,” saID Dr Eve Warburton, director of the Australia National University’s Indonesia Institute.

A generation with no memory of the 1980s and ’90s

Prabowo wanted to reach out a generation that has no memory of the 1980s and 1990s when President Suharto was in power and he was accused of human rights abuses.

Prabowo admitted to al Jazeera in 2014 that he had ordered the abduction of activists as commanded by his superiors in 1998 but had nothing to do with their disappearances.

While the older generation remembers those days, young voters say they would rather judge Prabowo on how he tackles unemployment and the cost of living, reported the BBC.

He clearly struck a chord with the young.

Exit polls conducted by Kompas newspaper’s research arm found that 65.9 per cent of Gen Z voters under the age of 26 voted for Prabowo. By comparison, 43.1 per cent of baby boomers aged 56-74 cast their ballots for him.

The exit polls indicated that young people had helped Prabowo cross the 50 per cent mark needed to win, Warburton said.

Prabowo’s earlier life

Prabowo was born in 1951 to one of Indonesia’s most powerful families. His father, Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, an economist, was a minister under Presidents Sukarno and Suharto.

However, his father turned against Sukarno and went into exile with his family.

Prabowo spent most of his childhood overseas – in Switzerland, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and the United Kingdom — and speaks French, German, English and Dutch.

The family returned to Indonesia after General Suharto came to power in 1967.

Prabowo enrolled in Indonesia’s military academy and served in the armed forces for nearly three decades. He became a commander of the special force called Kopassus, which was accused of human rights abuses.

In 1983, he married the then president Suharto’s daughter, Siti Hediati Hariyadi. They separated in 1998, the year Suharto died.

Prabowo was discharged from the military in 1998 after Kopassus soldiers kidnapped and tortured political opponents of Suharto. Some are still missing.

Prabowo admitted to Al Jazeera in 2014 that he had ordered the abduction of activists as commanded by his superiors in 1998 but had nothing to do with their disappearances.

He went into self-exile in Jordan in 1998 but returned to Indonesia in 2008 and helped found the Gerindra party.

Enjoying this article?

Subscribe to get more stories like this delivered to your inbox.

His plans as president

As president, he has pledged to continue Widodo’s economic development plans, which used the country’s large nickel, coal, oil, and gas reserves to fuel a decade of rapid growth and modernization that vastly expanded its roads and railways.

The new leader is also expected to continue Widodo’s extensive social assistance programmes for the poor.

Moreover, Prabowo has promised a free meal scheme for Indonesia’s 83 million schoolchildren, which is expected to cost more than US$27 billion annually. He has also promised three million new houses.

It is noteworthy how Prabowo has been consensus-building in recent months, forming alliances with political parties that once opposed him. He is now backed by seven parties controlling 82 per cent of the parliamentary seats.

Only the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), the country’s erstwhile ruling party, remains outside his camp.

In an almost hourlong wide-ranging speech to lawmakers on his inauguration, the new president vowed to root out corruption and said that while he wanted to live in a democracy, it must be “polite”, reported CNN.

What will truly distinguish Prabowo from Widodo is his approach to foreign policy, said the South China Morning Post (SCMP). Under the multilingual Prabowo, who has visited over a dozen countries in Asia and Europe since his election win in February, Indonesia’s foreign policy is expected to become more proactive.

Prabowo’s first overseas trip after his election victory was to Beijing in April, where he met President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang.

However, observers expect Prabowo to continue Indonesia’s non-aligned foreign policy, maintaining equipoise between Beijing and Washington, the SCMP added.

Senoir Editor