Hot this week

Last year's odd economy in five charts, and what to watch for in 2026

The growing Gen Z gender divide reshaping politics

USA & UK

Greenland: Trump's predatory mood

US President Donald Trump's attempt to "grab" Greenland constitutes a neo-colonial effort by a global "sheriff" who clearly does not respect the...

Trump’s Unmistakable Warning through Maduro’s Capture: Don’t Play Games

The capture of Nicolás Maduro marks the pinnacle of President Trump’s strategic power calculations and a manifestation of Washington’s unwavering...

Federal immigration officers shoot and wound 2 people in Portland, Oregon, authorities say

By CLAIRE RUSH and GENE JOHNSON Associated PressPORTLAND, Ore. (AP) — Federal immigration officers shot and wounded two people in a vehicle outside a...

How Delcy Rodríguez courted Donald Trump and rose to power in Venezuela

By JOSHUA GOODMAN Associated PressMIAMI (AP) — In 2017, as political outsider Donald Trump headed to Washington, Delcy Rodríguez spotted an...

US expands list of countries whose citizens must pay up to $15,000 bonds to apply for visas

By MATTHEW LEE AP Diplomatic WriterWASHINGTON (AP) — The Trump administration has added seven countries, including five in Africa, to the list of...

After capture and removal, Venezuela's Maduro is being held at notorious Brooklyn jail

By MICHAEL R. SISAK and LARRY NEUMEISTER Associated PressNEW YORK (AP) — The Brooklyn jail holding Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro is a facility...

UK

Prince William offers support for Epstein's victims as fresh disclosures reveal extent of his crimes

UK leader Starmer fights for his job as Mandelson-Epstein revelations spark a crisis

Violent, racist attacks overwhelm the United Kingdom

The pay-off: UK’s Liberal Democrats go for rich seats and win big

Donald Trump congratulates Nigel Farage but ignores Britain’s new Prime Minister Keir Starmer

Starmer wanted U.K. ‘weaned off’ China, now move to overhaul relationship

What did Rishi Sunak sacrifice as a child? Sky TV, he says

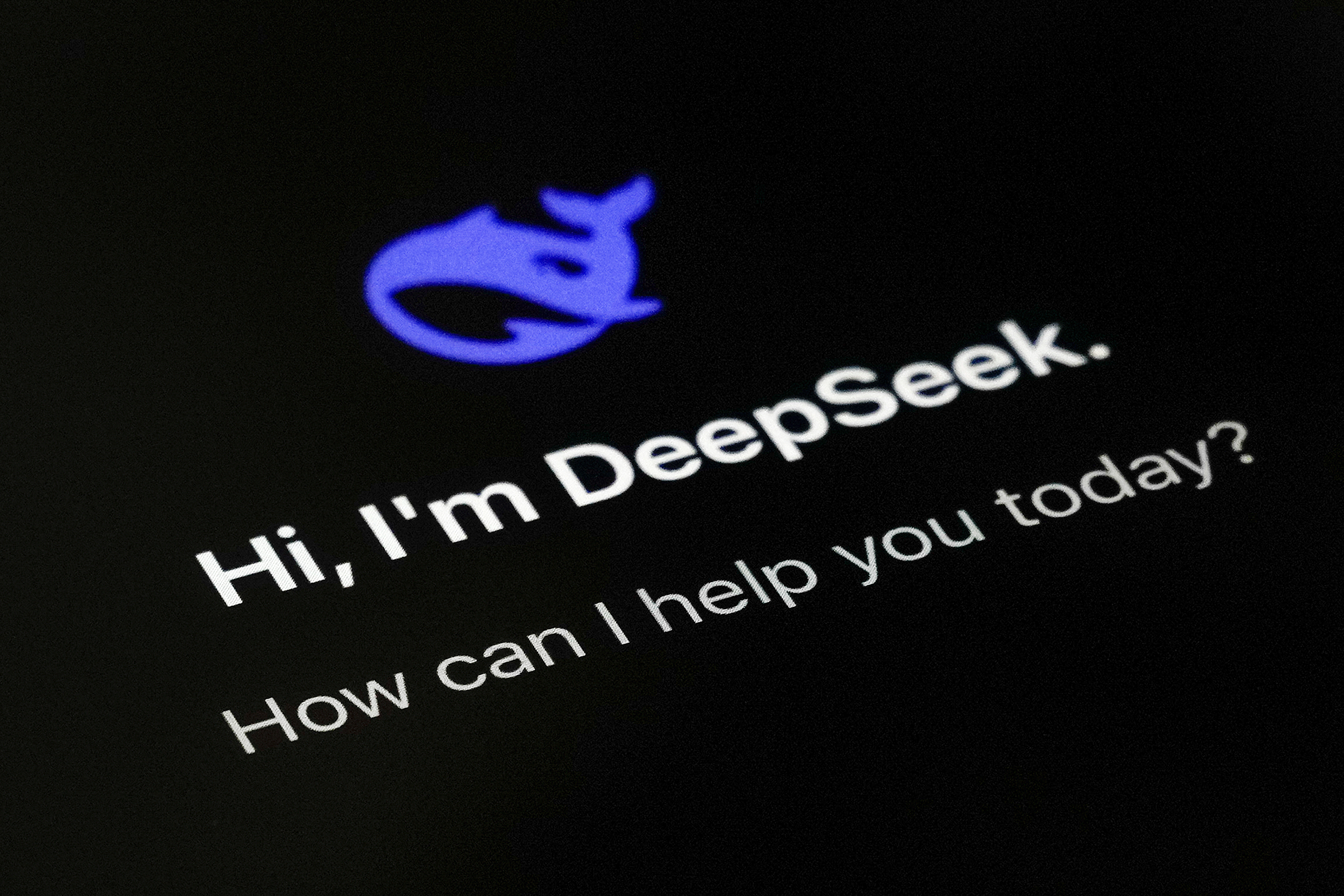

Technology

DeepSeek's AI gains traction in developing nations, Microsoft report says

Meta buys startup Manus in latest move to advance its artificial intelligence efforts

Supply Chain Cybersecurity Highlights the Need for Zero-Trust Cybersecurity

2026: Identity, Trust and the Rise of the “My AI Did It” Excuse

Travel

New data: APAC's three business travel profiles shaping 2026

Lifestyle

Taste of Brunei to Tempt Singaporean Foodies at Inaugural Brunei Week

Philippines’ Largest Shawarma Chain Plants Flag in Singapore, Eyes Global Expansion

Steigen: The Smart, Eco-Friendly Solution for Busy Professionals Who Want to Save Time on Laundry

Elon Musk’s daughter calls him pathetic, says he is a serial adulterer

Extreme frugality: The way to early retirement?

Celebrity

Has Renée Zellweger’s facial transformation been fueled by time, weight loss, or cosmetic enhancements?

Sports

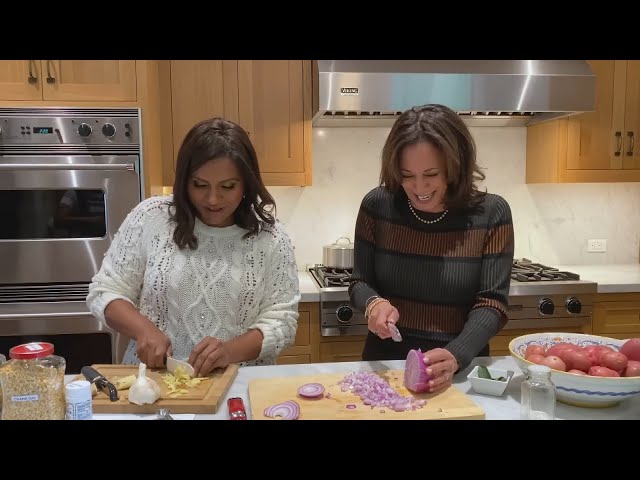

Kamala Harris visits US Olympic basketball team

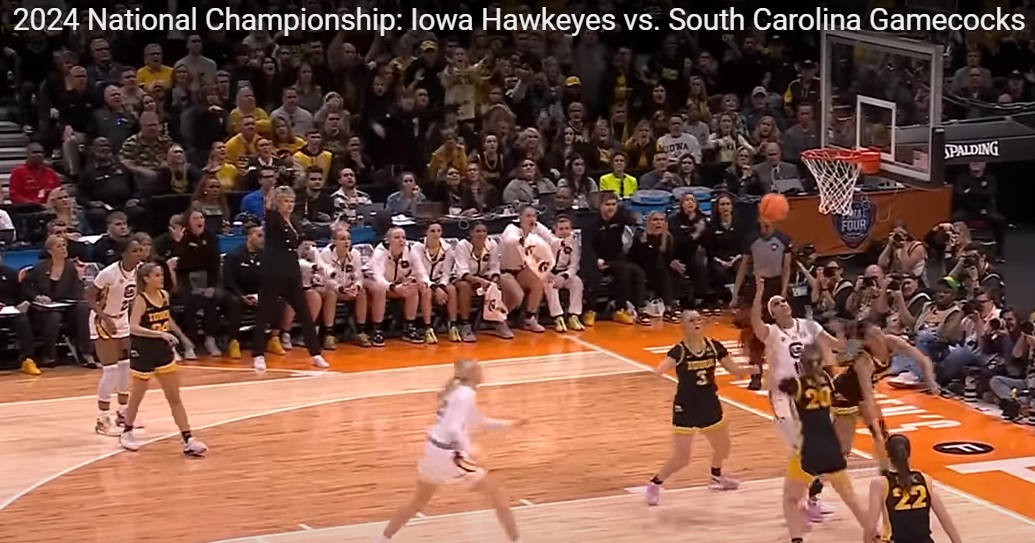

How did the Gamecocks triumph captivated audiences like never before

Russia and Canada submit appeals against the 2022 Winter Olympic team ranking

Paavo Nurmi, aka “Flying Finn,” will showcase his five gold medals once more at the 2024 Paris Olympics.

USA women’s Olympic gymnastics squad, including Simone Biles, Suni Lee, and Kayla Di Cello

Personal Finance

Gen Y: Maintaining financial resilience during Australia’s economic downturn

Evergreen

From outcast to overlord – How a child kicked out of Macao’s elite hotel now calls the shots

China & Hong Kong

Caring Robots: A new solution for aging societies?

In a care facility in eastern China’s Jiangsu province, a waist-high white robot glides quietly...

Inside China’s biggest show: What it says about the country

For millions of people in China, Chinese New Year’s Eve begins the same way: a long journey home, a...

Keeping one-fifth of humanity warm

Winter has a way of stripping systems down to their essentials. Pipes freeze. Power lines snap....

Galloping through cultures: How horses connect humanity

Every time the Chinese New Year approaches, I find myself paying closer attention to the animal of...

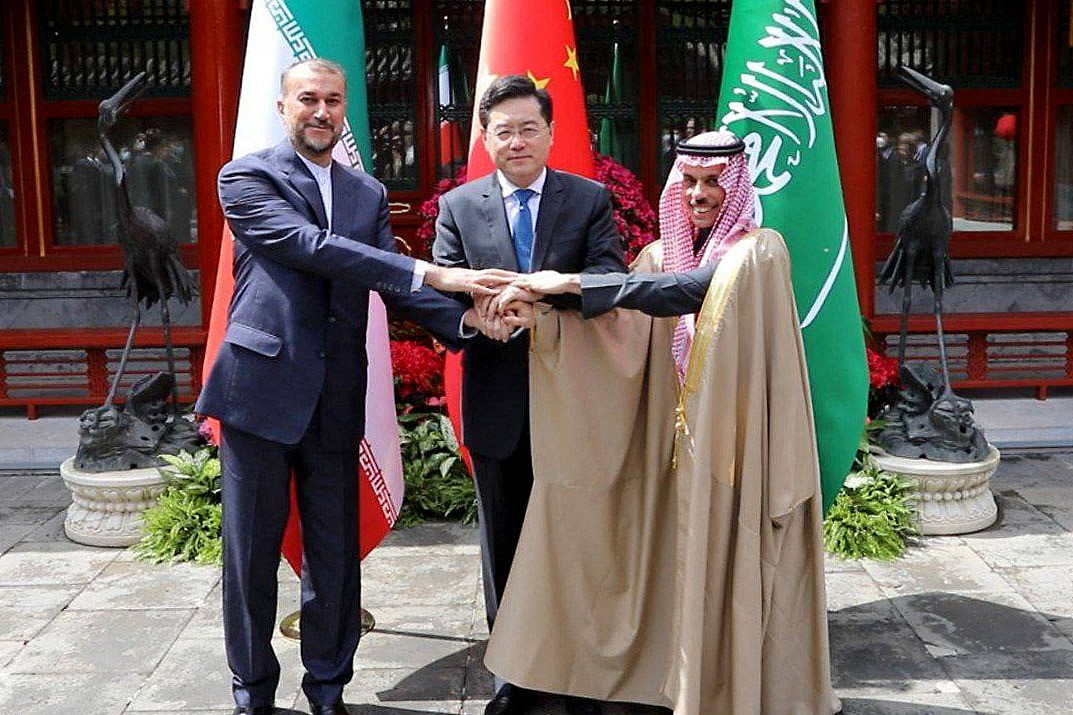

Pushed by Trump, US allies are resetting relations with China

Chinese President Xi Jinping has had a busy few weeks receiving Western allies seeking warmer ties...

What does “common security” really mean today?

By Niu Honglin As a podcaster, I work on shows with different themes. Some are analytical. Some are...

How will “a shared future” save the world from fragmentation?

By Niu Honglin, CGTNWhen I was working on this new podcast, one question kept showing up in my...

Hong Kong High Court Convicts Lai Chee-Ying of Collusion to Endanger National Security

HONG KONG SAR - The Court of First Instance of the High Court of the Hong Kong Special...

How and Why does China Host a "Domestic Olympics"?

The article offers a timely and insightful look into China's ongoing 15th National Games, an event...

Beijing warns Tokyo of a 'painful price' as Japan pushes missile line toward Taiwan, escalating Asia’s sharpest strategic standoff in years

BEIJING: China’s Defence Ministry delivered a sharp warning to Japan in November 2025, saying Tokyo...

Chinese research vessels operate in Northwest Pacific amid U.S. military drills, raising security concerns

Five Chinese research vessels quietly made their way through the northwest Pacific, their missions...

SUV rams into students and pedestrians outside primary school in China, sparking concern over rising violence

A new incident outside a primary school in Changde, southern China, has added to growing concerns...